An Introduction from the Editor

Called the ‘Great War’, it was a name which described the extensive destruction and impact it left on the world. Highlighting the mass carnage of World War One, when the Battle of the Somme began at 07:30 on 1 July 1916 – following a brief and eerie silence as tens of thousands of men considered their fate in the next few minutes – whistles blew and the first British and French infantrymen left their muddy trenches to meet a deadly hail of machine-gun fire. By the end of this first day the British alone had almost 20,000 men killed, over 35,000 wounded, more than 2000 missing and hundreds more taken prisoner – the total loss was almost 60,000 in just one day and the offensive was to go on until November.

Above the devastation of the trenches, a new form of warfare had been rapidly evolving in the air which was transforming military strategy. Planning for the Somme offensive was based on the aerial reconnaissance photographs provided by the Royal Flying Corps. ‘Winged’ warriors were now duelling in the sky, which was their very own field of honour where they often fought by a gentleman’s code that would seldom be repeated in modern warfare. This chivalry in the air contrasted with the slaughter below, although war it still was and many young and inexperienced airmen were killed within days of their arrival on the front line. During the months of the Somme offensive almost 800 aircraft were lost, taking with them the lives of hundreds of airmen. These early flyers certainly played their part in the eventual Allied victory.

Flying in fragile fabric-covered aircraft, being shot at from the air and ground and without parachutes, the risks were high. There are some incredible stories of courage from this period though, as is evident with those of Alan Arnett McCleod and Albert Ball who both feature in this issue of Aviation Classics.

As a boy I became fascinated with the aerial conflict of World War One after watching classic films such as The Blue Max and Aces High. I built models of an all red Albatros and Sopwith Camel and remember spending hours on the stairway landing playing out dogfights between the two. Later I read much about the exploits of the daring early military airmen of the era and was often left in awe of their bravery and achievements in the line of duty. It only further fuelled my desire to join the Royal Air Force, which had been established during this conflict on 1 April 1918.

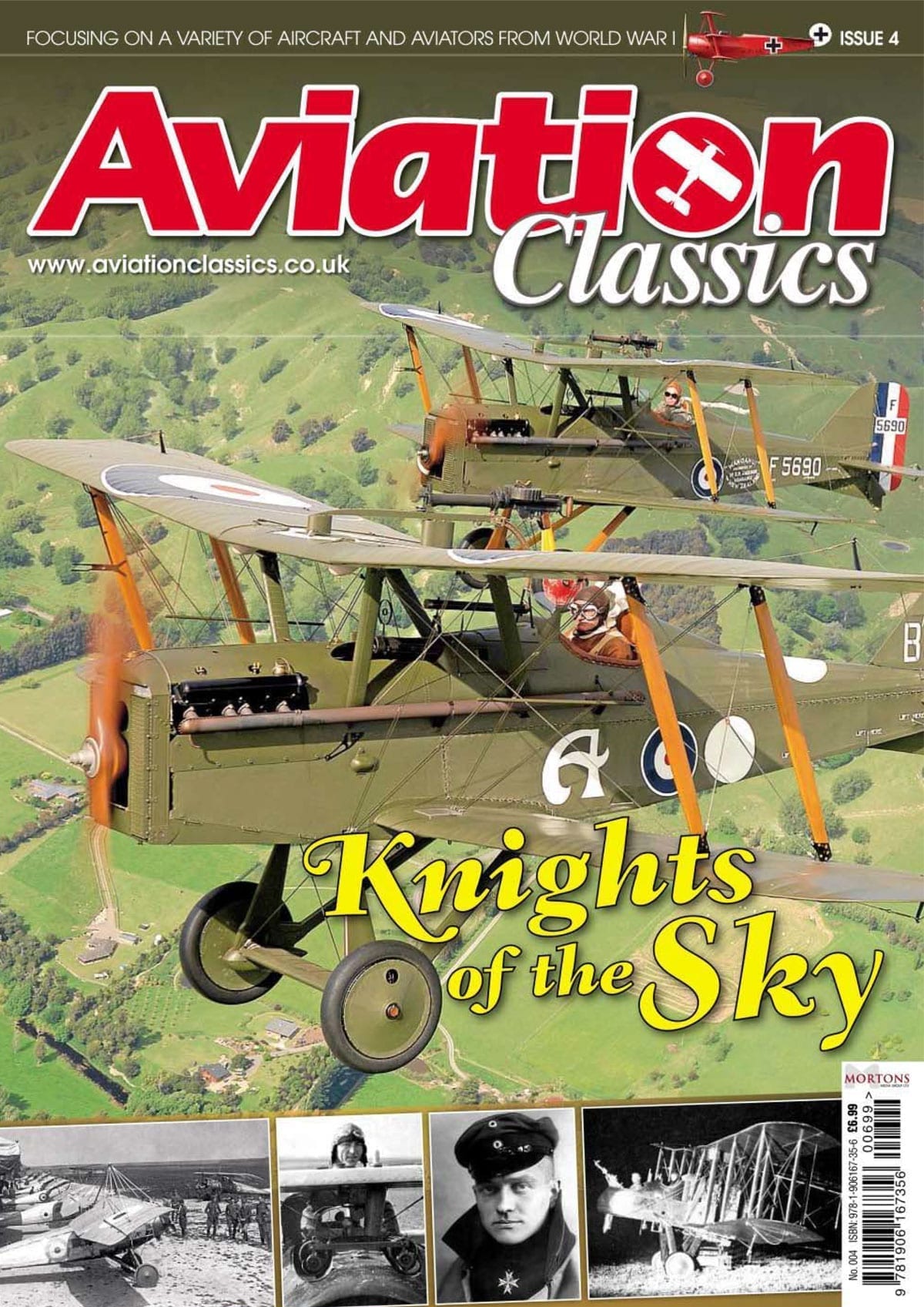

Today’s airshow audiences can see this aspect of the evolution of military aviation well represented the world over. For example, in the UK the Shuttleworth Collection has a wonderful fleet of 1914 – 1918 period machines. In the USA there are numerous airworthy World War One types at Old Rhinebeck. Over in New Zealand The Vintage Aviator Ltd has in the past few years made great progress with both the restoration of original aircraft and the multiple construction of perfect reproductions of types from the era.

I was invited out to witness the results and the reproduction Albatros D.Va that was about to fly particularly caught my eye. It has been built to exact specifications and is powered by an original engine, so is as close to seeing an original Albatros D.Va fly as can be. Add to that TVAL’s superb Sopwith Camel and it all brings to life those model dogfights of my youth.

I’d very much like to thank the following at TVAL for all their assistance and kindness in many ways during my visit to gather material for this issue: Gene DeMarco, Tim Sullivan, Stuart Goldspink, Keith Skilling, John Bargh, Gary Yardley, David Cretchley and – last but certainly by no means least – camera ship pilot Kerry Conner. Without their passion to showcase these wonderful aircraft to a wide audience this issue would not have been possible.

Author: Jarrod Cotter